Asymmetrical Re-Worlding, Part 4: The End of Male Power | by Therese Doherty

Subscribe between now and Halloween, and get six months of a $12 rate for $8, includes private event invites, first event just after Halloween, two more in winter.

(. ❛ ᴗ ❛.) Or, just leave us a tip. (. ❛ ᴗ ❛.)

We do love to pay these writers, reporters, artists.

Previously: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3

Part 4: The End of Male Power

According to the postfeminists that I am refuting in this series of essays, men are dominant and women are submissive; men lead and women follow; men protect and provide and women simply have babies. And this is all, seemingly, ‘natural’, ‘biological’ and ‘instinctive’, as if Evolution hardwired us that way. Yet there is much evidence—from anthropology, primatology, zoology, sociology and other fields (as well as good old common sense)—that disproves these claims, overturns what we think of as ‘natural’, and emphasises how adaptable living beings really are. As humans, we have the ability to consciously choose to organise our cultures in ways that prioritise the care of children and other vulnerable people, based on partnership between the sexes, rather than relationships of hierarchy and domination.

Though it wasn’t new information, research was published in April 2025 about how female bonobos form coalitions in order to suppress male dominance. With their high status and easy sexual autonomy, they maintain freedom and authority, despite being smaller than males. This female social ‘dominance’, according to primatologist and ethologist Frans de Waal, ‘is largely based on seniority rather than physical intimidation’.[1] That is, it takes a very different form to male dominance. The system of matriarchy is not the polar opposite of patriarchy, it’s an entirely different paradigm. As I wrote in Part 3, it’s a system in which children are raised communally and grow up caring for their mother’s land; women have autonomy and are not subjugated to men (sexually or otherwise); a general egalitarian ethos prevails; and it is understood that women, as the progenitors of life, are also the creators of culture, and are respected accordingly. If we’d discovered the easy-going matriarchal bonobos first, and not the more hierarchical chimpanzees or baboons, de Waal speculates, ‘We would at present most likely believe that early hominids lived in female-centered societies, in which sex served important social functions and in which warfare was rare or absent’.[2]

Female coalitions overcoming male dominance brings me to the intriguing work of anthropologist Chris Knight who develops a theory of human cultural origins based on exactly that. He argues that females developed solidarity due to their propensity for menstrual synchrony, and evolved a form of ‘sexual morality’[3] based on what, from his Marxist perspective, he calls the ‘sexual picket line’ or the ‘sex strike’. The female necessity of sexual autonomy—of being able to say ‘no’—and the formation of alliances with male kin as well as, importantly, other non-dominant, cooperative males, is what ultimately humanised the species and enabled culture to come about. This is because hungry, vulnerable ‘Babies’, not men, ‘would ultimately have had to come first. Sex would have had to be subordinated to economics.’[4] Knight says,

male dominance had to be overthrown because the unending prioritising of male short-term sexual interests could lead only to the permanence and institutionalisation of behavioural conflict between the sexes, between the generations and also between rival males. If the symbolic, cultural domain was to emerge, what was needed was a political collectivity – an alliance – capable of transcending such conflicts.[5]

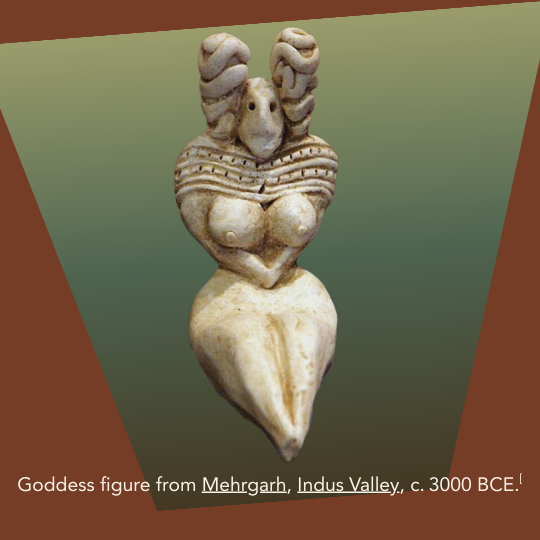

Female solidarity and the prioritisation of the needs of mothers and children, founded on blood mysteries and matrilineal kinship, transcended male power and desires. Egalitarianism, it has been argued, was a prerequisite for language development and culture formation. Male dominance and female submission are the antithesis of human culture. The development of patriarchy was a very recent devolution for our species, a usurpation of already-existing female cultural creativity and authority, and that’s why the female collectivity of feminism and gynocentric social structures are so threatening to men—and to postfeminist women. Knight affirms: ‘Far from producing culture … male power enters tardily on to the scene, transforming and politically colonising a cultural landscape long since formed by others.’[6] The Mother Goddess was murdered and replaced with the fabricated Father God.

The story of human origins is complex, and there is much that we can only speculate about. I am not claiming that Knight’s theory is correct in all of its aspects, nor that we should extrapolate directly from either primatological or anthropological studies to explain modern humans, but such ideas do help us to think outside of the patriarchal narrative. And my Goddess! Things were better once upon a time, before men invented patriarchy, and everything went to hell. ‘[W]hat one imagines to have existed in the past, in a Golden Age,’ says Susan Griffin, ‘stands in the mind for the hope of wholeness we might be able to find in the future. To consider the possibility of matriarchy requires a shift in thinking.’[7]

The world that feminists want to (re)create is a world beyond any kind of dominance hierarchy, where everyone is valued and cared for according to need, rather than one based on the production of surplus value for those higher up, and on violence and exploitation. In terms of the abolition of gender, this means not the elimination of sexual difference, but the end of the unjust and erroneous hierarchy of values assigned to the sexes, and the end of power imbalances in relationships. The aim ‘is to destroy male power itself.’[8] As Riane Eisler contends, the way we perceive the mother-child relationship might be a residue of pre-patriarchal understanding, for it’s

the one human relationship that even in male-dominant societies is not generally conceptualized in superiority-inferiority terms … The larger, stronger adult mother is clearly, in hierarchic terms, superior to the smaller, weaker child. But this does not mean we normally think of the child as inferior or less valued.[9]

There is a saying—there are only two kinds of people in the world: mothers and their children. The vision of matriarchy centres women~children~Earth. While not all women become mothers, we were all once children, so everyone is embraced in that analogy, including men.

According to artist/writer/ecofeminist Monica Sjöö and poet/editor/Goddess feminist Barbara Mor, who together produced the groundbreaking cross-disciplinary (and must-read!) book of feminist revisionist history, The Great Cosmic Mother, matriarchy was a holistic cultural system in which

Women owned their bodies, their children, and their living properties; women made vital decisions affecting the survival and well-being of their people. There was no way by which an elite group of men could set up laws to restrict women's movements, ideas, or sexual activities. Economic relations were not experienced as separate from religious and social relationships; they were originally based on gift exchange, which served a communal-bonding function, not a competitive or profit-making one.[10]

Socialisation is the primary cause of behavioural dysfunction, and the underlying cultural conditions that we all have to contend with are traumatising, thus I don’t believe that men are innately violent or irredeemable—that’s actually one of the patriarchal myths we need to overcome, for it justifies their continued misbehaviour (the myth of male dominance actually insults and inhibits men). ‘In its classic form of perverting what is right and healthful into a tool of domination,’ Esmée Streachailt writes, ‘patriarchy puts humans into a bad paradox “of forcing a sacrifice of relationship in order to have relationships” by separating boys and girls from essential parts of their being’.[11] The indoctrination of gender, the dualistic fragmentation of the world, and the myths of civilisation ‘wire’ us in ways that influence who we become. The bodymind is permeable, because we are ecological beings embedded in an ecosystem of diverse influences, and the cultural predominance of gender means that false beliefs take over. Yet because the social context and our bodyminds are mutually reinforcing, Cordelia Fine’s conclusion is encouraging: ‘As society slowly changes, so too do the differences between male and female selves, abilities, emotions, values, interests, hormones and brains’.[12]

If we can start to tell new cultural stories at scale—about matriarchy, about egalitarianism, about mutuality, about peace—and begin to enact them, then perhaps we can move towards a better future. We need new-old stories that intertwine us all into relationship with each other and the Earth. It’s therefore essential that women cast off the patriarchal myths that clothe us and society with male-defined assumptions, and rediscover our herstory.[13] But getting beyond our cultural indoctrination isn’t easy.

Patriarchy has four core elements according to Max Dashu:

sexual control, control of women’s procreative power, and exploitation of women’s labour … [and] the psychic colonization of women. The internal mental induction of women into patriarchal behaviours and allegiances, by means of culture, whether that’s romance novels, magazines, or religious dogma, you name it.[14]

This psychic colonisation is exemplified by the fairytale princess who waits patiently, passively and powerlessly, to be rescued by the all-conquering heroic prince. As Sharon Blackie points out, in Joseph Campbell’s vision of the hero’s journey ‘women can be no more than the destination: we represent the static, essential qualities that the active, all-conquering Hero is searching for; we’re considered only in the context of what we represent for the male Hero’. The post-heroic journey that Blackie outlines provides an antidote to this stultification, but I particularly like Streachailt’s formulation:

The Hero's Journey might be to Go Out and return to the Origin, but the Heroine doesn't return. “A girl's journey is farther—to the unknown, to invent” possible and desirable metaphors, worlds. If one must go out through a door or a gate, the (metaphysical or archetypal) Masculine seeks to return through that same gate or door. The Feminine? She never wants to see that place again.

‘Re-worlding’, Streachailt says, ‘is another way to phrase the project of radical feminism’.[15] Once the heroine knows that other worlds exist, or are possible, there’s no going back. To quote Ursula K. Le Guin: ‘We are volcanoes. When we women offer our experience as our truth, as human truth, all the maps change. There are new mountains.’

Many women are limiting their interactions with men via various separatist strategies, which I respect, but we can’t stop there. While we must protect our wellbeing in the short-term, we can also be considering longer-term goals. We need to offer a new human story that includes men too. Healthy socialisation for boys, particularly in the early years of life, is critical, because

Once beyond the age of malleability, males seem to be stuck with whatever imprint they’ve received … If the influences during this “developmental window” are distorting and destructive, a boy may grow into a man with an unalterable, nearly irresistible desire to reenact the same patterns with others.[16]

Campbell’s conception of the hero’s journey is patriarchal in origin, and doesn’t offer what is needed. Compare it with Heide Goettner-Abendroth’s evocation of the older Greek word heros— the Sacred King of matriarchy, who, ‘lives and works within the cosmic ordering of life, and represents, through the Goddess, masculine creativity’. He makes a cyclical journey into the Underworld from which he is reborn. This is ‘a voluntary sacrifice on behalf of land and people, so that in following the laws of the cosmos, new life is made possible’. In contrast, the patriarchal hero

has been wrenched from his close connection with the Goddess and with nature. To achieve his meaningless heroic deeds he now destroys nature and other human beings … The sacrifice of the* heros*, on the other hand, is made out of love for the Goddess and nature, and he goes into the Underworld in order to be born again through her.[17]

This sounds much more like Blackie’s post-heroic journey, though it’s almost pre-heroic, rooted in the shamanic Underworld journey, deference to Mother Nature and Her cyclical round of life~death~rebirth.

In one sense the postfeminists are right—we do need to earth back into our female bodies which are part of nature—but they neglect to mention that men need to do the same. In fact, it might be even more crucial that they become embodied, because ‘the problem is not that women are closer to nature than men’. As Jane Clare Jones points out, ‘ The problem is that men staked an entire society on the pretence that they are not part of nature’,[18] and we’re all paying the price for this disastrous error.

Men are their bodies just as women are, and without wholesale change to male attitudes and behaviour, without men developing sexual self-restraint and the maturity to actually see women as human—without rooting back into empathetic ways of relating—there can be no positive change. Men need to give up their dominance and sense of impermeability, their abstractions that alienate them from material reality, and embrace their softness, vulnerability and dependence on the mothers that birthed them and the Earth that sustains them. We’re all flesh and blood beings, we’re all part of nature. We will all die and be regenerated into other life. ‘Only when the two sexes can communicate in the absence of one-sided violence or power privileges which exempt men from having to think at all in relation to vast areas of sexual, personal and family life’, Knight says, ‘only then will sanity and objectivity in cross-gender communication systems have some chance of arising.[19]

Women are beginning to create a new-old matriarchy, and if men refuse to pay attention, if they refuse to listen and learn and contribute, they’ll simply be left alone and lonely in their dying patriarchy. Ultimately, the Goddess is the process of Evolution, and Evolution has one rule: adapt or die.

Therese Doherty lives with chronic illness and occasionally writes and makes art, but mostly just reads a lot. She can be found here: @offeringsfromthewellspring.

Christopher Ryan & Cacilda Jethá, Sex at Dawn: How We Mate, Why We Stray, and What It Means for Modern Relationships, Harper Perennial: New York, 2010/2012, p. 71 (pdf page number) ↩︎

Ryan & Jethá, p. 70 (pdf page number) ↩︎

‘For the first culturally organised humans, sexuality could no longer be under purely personal control. The availability of one’s body was of potential concern to the whole group. There were elements of repression in this … But there was nothing necessarily patriarchal about the repressive forces which now came into play. The culturally necessary inhibitions came from within. Contrary to the Victorian myths, so-called “modesty” or “morality” had not been imposed on earliest women by men: women had imposed it on themselves (producing mirror-image responses among culturally organised men) as a condition of their own solidarity and power.’ Chris Knight, Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture, Yale University Press: New Haven, 1991, p. 43 (ebook page number) ↩︎

Knight, p. 42 (ebook page number) ↩︎

Knight, p. 670 (ebook page number) – According to Knight’s theory, females instituted a taboo on sex during their synchronised menstruation as a strategy to encourage men to band together to hunt, and then bring back meat to share. When men returned, and women’s bleeding had ended, sex and feasting would result. There’s obviously a lot more detail that I can’t share here, but the concept of female solidity being what essentially humanised the male and led to culture formation, is what is directly relevant to my argument. ↩︎

Knight, p. 668 (ebook page number) ↩︎

Susan Griffin, Made From This Earth: An Anthology of Writings, Harper & Row: New York, 1982, p. 14 ↩︎

Françoise d’Eaubonne (translated and edited by Ruth Hottell), Feminism or Death, Verso: London, 2022, p. 67 – find this book in the Radical Feminist Library ↩︎

Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future, HarperOne: New York, 1987/1995, pp. 27–28 ↩︎

Monica Sjöö & Barbara Mor, The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering the Religion of the Earth, HarperOne: San Francisco, 1987/1991, p. 19 – find this book in the Radical Feminist Library ↩︎

Esmée Streachailt, ‘Integration is the Radfem Way: A Review of In a Human Voice’, THE RADICAL NOTION, Issue Twelve (Autumn/Winter 2024), p. 103 – all issues are available to read online or download for free here: https://theradicalnotion.org/ ↩︎

Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences, Icon Books: London, 2010, p. 161 (pdf page number) – find this book in the Radical Feminist Library ↩︎

Max Dashu’s work for more than half a century on the Suppressed Histories Archives is one of the treasures we can refer to. Sylvia Linsteadt’s writing, revisioning myth with a feminist and ecological perspective, is also highly recommended, as is Renée Gerlich’s Brief Complete Herstory, serialised on Substack. ↩︎

Jane Clare Jones, ‘Matricultures and the Matrix of Life: An Interview With Max Dashu’, THE RADICAL NOTION, Issue Six (Winter 2022), p. 100 ↩︎

Esmée Streachailt, ‘Re: Framing Radical Feminism: Luce Irigaray and Being Beyond Patriarchy’, THE RADICAL NOTION, Issue Nine (Spring/Summer 2023), p. 75 ↩︎

Ryan & Jethá, p. 251 (pdf page number) ↩︎

Heide Göttner-Abendroth (translated by Lilian Friedberg), The Goddess and Her Heros, Anthony Publishing Company: Stow, Massachusetts, 1995, p. 5 ↩︎

Jane Clare Jones, ‘Editorial Statement: Women and Nature’, THE RADICAL NOTION, Issue Six (Winter 2022), p. 5 ↩︎

Knight, p. 674 (ebook page number) ↩︎

Reach out anytime for any reason: info@medusarising.org.

( ^-^)ノ∠※。.:*:・'°☆ ( ^-^)ノ∠※。.:*:・'°☆ ( ^-^)ノ∠※。.:*:・'°☆