Hyperlithic Colours Gorgon | by Victoria Gugenheim

Introducing the new Medusa Rising Legacy Palette and its ancient, powerful origins

When building the world we want to see, visual colour language is usually is not a high priority in contemporary radical feminist circles aside from the suffragette palette point as it does to (and importantly so) policies and politics. But colour is connection, it's actually of significant psychological importance, and one of the core reasons I selected the pigments in this graphic to be the new additions to the Medusa Rising Magic Milieu ♪┌|∵|┘♪

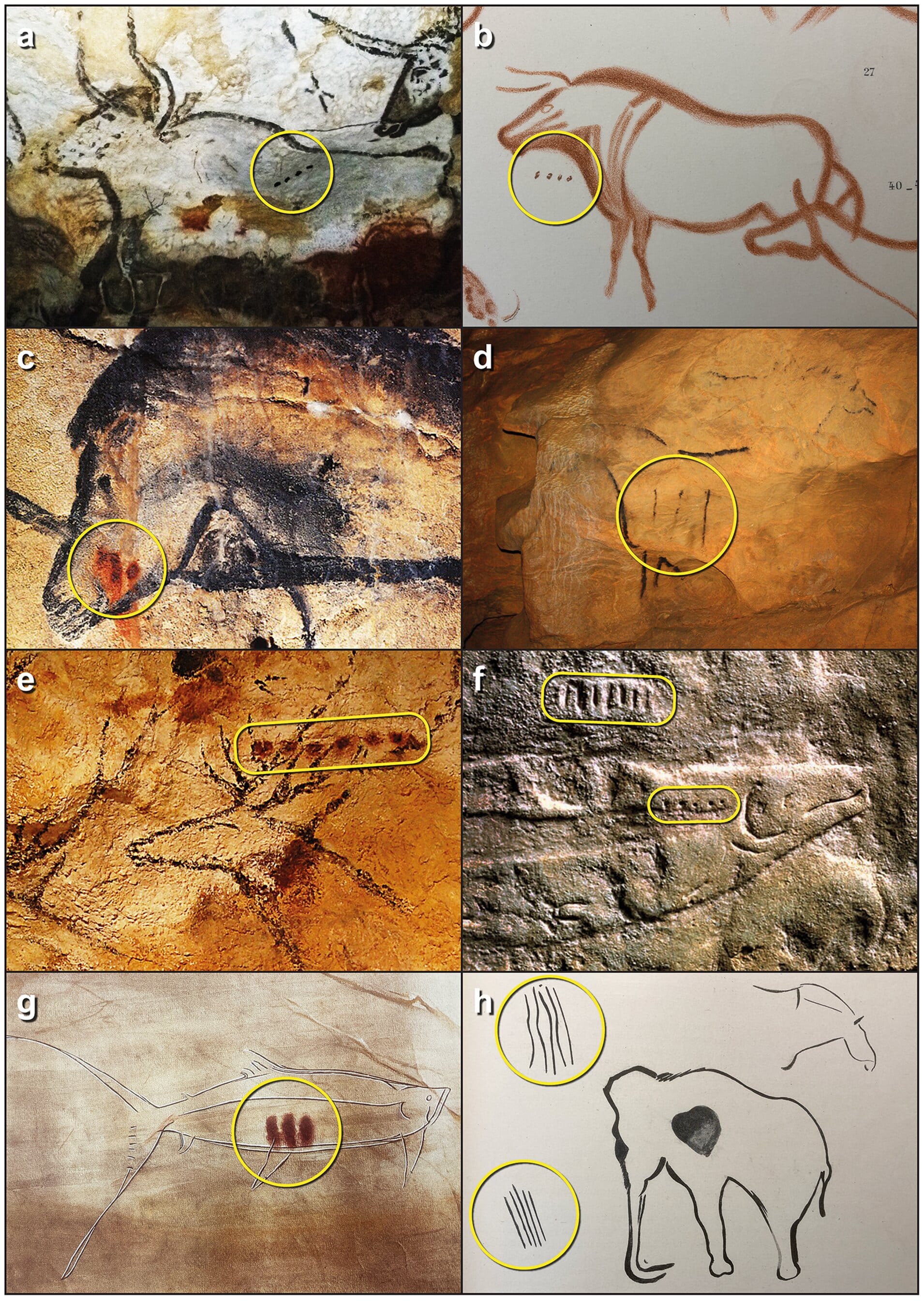

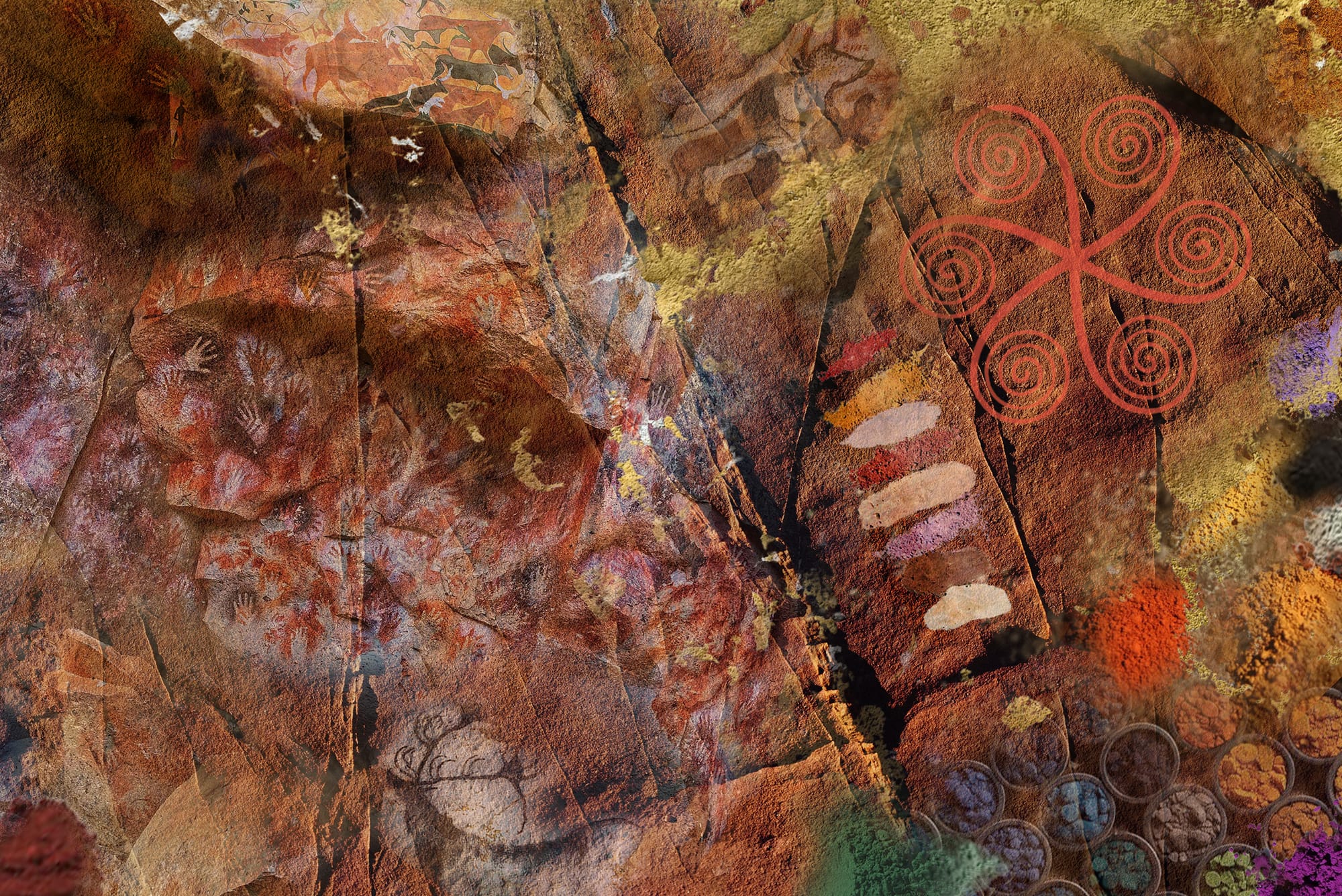

The original pigments of the palette here were conceived, were created directly from the earth, by our Paleolithic ancestors and are a potent reminder that all of us witnessing them now come from a long, unbroken line connecting us with both our deep, vast ancestral lineage and the planet we live on through a livid legacy of vibrant, connected colour, created, discovered and explored before patriarchy became de rigeur through warfare and rape after farming made it feasible. The art created with them, beginning 64,000 years ago before exploding at 50,000 BP all across the planet through unconnected tribes as our burgeoning, emergent complexity as a species, finally allowed us permanent expressive visualisations of our lives and meanings and these pigments even appeared on the first calendar carved deep into cave walls so our female ancestors could track their menstrual cycles (because which man generally needs to track 28 days, exactly?).

These pigments are a part of arguably, the very first consequence-free experimentation (people worked out which pigments were toxic over 60,000 years ago). If a new hunting or gathering technique was tried and failed, people might not eat, whereas a (possibly resident) cave painter would instead, be able to wipe off the spit paint and pigments and try again. No lives were lost, no stomachs left rumbling, just the ability to start anew on cave as canvas. This was a phenomenal step in our evolution to be able to think on a scale with this level of safety, flow and play, ensuring that we had time not just to survive, but alongside carving, knapping and craft, to creatively cognize, and from this, our ability to start to abstract, visualise and create further complex culture followed. It's also one of the first documentations we have of experiencing and communicating vital elements of a functioning society, namely empathy and compassion. It's only fitting that our Gorgon palette comes from this crucial step in our cultural evolution as we create a cultural revolution.

Another fitting finding we can't ignore is that the great majority of cave painters appear to have been female, discerned through looking at hand prints in Stone Age cave sites where the similar length between index and ring fingers in the prints and vermillion spit-painted outlines, clearly demonstrate three quarters of female handprints present in a time where sexual dimorphism was actually much more pronounced (and therefore easy to discern through handprint observation ) Women are natural creators, and it's time that we took that lineage back from a culture of erasure that would continue to oppress us, and build something creative, nurturing and beauteously weave from the margins, create from the corners.

The pigments used in ancient cave art are a component part of a vital step in our emerging properties of both civilisation and our evolution, when we first started creating solidified, complex societies, including even an emerging respect for the dead, signifying a budding spirituality, so let's take a Gorgon led journey into these pigmented wonders of the ancient world, and when they first emerged.

The Paleolithic era:

Middle to upper paleolithic era aka “The Stone Age” 40,000–15,000 BP (before present)

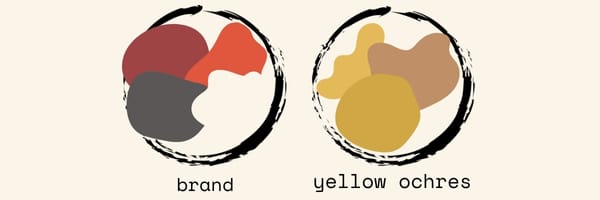

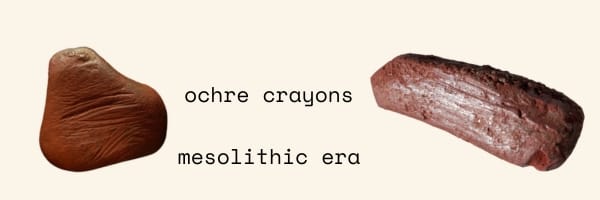

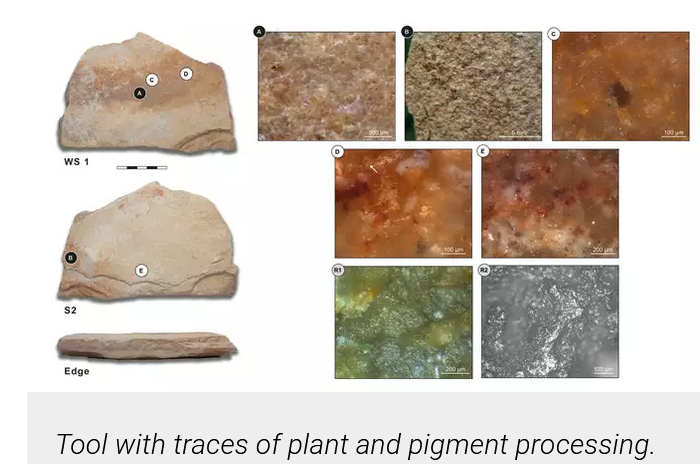

Red ochres (actually reddish brown) (a – sources below) -Pigment type: Iron oxides (haematite or goethite/limonite) -Made of: Naturally occurring iron oxide minerals (limonite for yellow ochre (more below); haematite for red ochre) oftentimes mixed with clay or sand. -Manufacture: Minerals were ground into fine powder using proto pestle and mortars (pictured below), washed, dried, and sometimes heated (“burned”) to deepen their hue and then mixed with binders (water, animal fats, blood, bone marrow, spit) to turn them into pastes or sticks (b)

Yellow ochres -Pigment type: Another type of Iron oxide (goethite / hydrated iron oxide) -Made of: Mineral limonite rich earth pigment (c) -Manufacture: Same procedure as for red ochre; ground into a powder and mixed to a paste or sticks with binders (d)

Original Carbon Black (original mid-dark black) -Pigment type: Carbon (charcoal or soot only, manganese did not emerge generally until Lascaux, approx 15000 BP, more later) -Made of: Charred wood/organic matter such as bone for charcoal (e) - Manufacture: Our sister ancestors would burn wood or bone to charcoal. Handlers then used organic binders; often used for outlining and hand stencilling (f)

Umbers/ Browns

-Pigment type: Mix of iron oxide + manganese oxide

-Made of: Earth with both iron and manganeseoxides (“raw umber”) (g)

-Manufacture: Ground, possibly heated to deepen, mixed with binder (h)

White and off-whites (calcite / kaolins) -Pigment type: Chalk / calcium carbonate or kaolin clay -Made of: Ground chalk (limestone), calcite deposits or kaolinite (i) -Manufacture: Powdered then used alone or as extender; mixed with binders or applied as light, ground up layers (j)

Violet / purple ochres (25,000 BP approx, sources: Pech Merle, Altamira, Lascaux) -Colour: Deep, rich violet to purple grey -Pigment types: Anhydrous iron oxide (specular haematite, a vivid, sparkly purple, rich type of haematite), also containing manganese minerals or larger haematite crystals -Made of: Natural ochre sediments rich in haematite with a coarse grain size, or specularite for the deeper purples, sometimes with traces of manganese -Manufacture: Collected ochre was extracted, crushed or ground (some sisters intentionally selecting coarser particles), and then pulverized—as evidenced by grinding tools. No heating needed. Mixed with water, fat, or saliva to form paint stick or paste. Used in cave art as rare violet tones or substitutes for black (k) (l).

Brown and red ochres are common; violet shades appear when hematite crystals are larger, yielding a cooler or purplish hue (m) (n). Pech Merle and other French sites contain evidence of dark violet hues applied using manganese-rich or specular hematite pigments, sometimes instead of charcoal black.

Later Prehistoric / Early Rock Art (e.g. Lascaux 15,000 BP)

Manganese based black (a very deep black/grey, can also sometimes have blue or violet under hues) -Pigment type: Inorganic manganese oxides/hydroxides (e.g pyrolusite, manganite, etc.) -Made of: Naturally occurring manganese minerals, sometimes sourced far from site (0) -Manufacture: Ground into fine powder and mixed with a binder; in some French caves (e.g. Lascaux) all black figures use mineral manganese as opposed to charcoal; this may signify that they were evolving their art, and as women have a greater colour vision than men, this would have mattered to female cave artists.

Green earth pigments (green) -Pigment type: Green earth pigment made from either celadonite or glauconite -Made of: Clay minerals (celadonite, glauconite) mixed with iron and magnesium silicate (p) -Manufacture: Mined, ground; sometimes mixed with yellow ochre for brightness; applied with binders (q) Regional, Later Rock Art (e.g. Cueva de las Manos, Patagonia, 9000BP )

Copper based green or yellow shades / Natrojarosite (yellow green)

-Pigment type: Copper oxide or iron sulfate mineral (Natrojarosite)

-Made of: Mined copper oxide or iron sulfate mineral, gypsum, kaolin, other earth minerals (r)

-Manufacture: Ground and mixed; gypsum often added as binder or extender to help adhesion

You can imagine the dedication that our ancestral artists would have had to creating the right tones, adding the right fillers, fats and binders, even finding ways to finesse and store them so they could create when they needed; when they wove stories, placed their palms to the stone to spit-paint, to capture the death of a loved one or a glyph to mark a place they called home. It is alive with the primal power of women who created and mothered as opposed to destroyed.

So now we have our visual lexicon that grounds us directly to the earth, a living palette that our sisters forged and finessed with their fingers, let's get to work creating a future worth cultivating, sisters.

Victoria Gugenheim is a contributing editor of Medusa Rising.

Editors Note: Male domination emerged in many places and ways at different times. In some, it was a response to climate caused privation. In others, it was a perverse response to abundance as hoarding and greed. It has not been with us since the earliest civilizations, and as far as we can tell was not part of life of the people who gifted us these glorious pigments and visions. The hard sciences are about 15 years behind the anthropologists on this one. Most scholars of matriarchies in Europe and around the Black and Caspian seas date the demotion of women to about 5 or 6000 years ago, as Gimbutas and Goettner-Abendroth hold and European DNA bears out. – ES

Pigment History/Manufacturing References:

(a) https://www.grunge.com/879444/what-was-used-as-paint-in-cave-paintings/

(b) eportfolios.capilanou.ca/marrincoulter/2022/10/03/the-cave-artists-tool-kit

(c) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-021-01397-y

(d) https://viva.pressbooks.pub/arthistory/chapter/cave-painting/

(e) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-021-01397-y

(f) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-021-01397-y

(g) https://www.howitworksdaily.com/prehistoric-painting

(h) https://www.pcimag.com/articles/86476-a-history-of-pigment-use-in-western-art-part-1

(i) https://www.pcimag.com/articles/86476-a-history-of-pigment-use-in-western-art-part-1

(j) https://www.mdpi.com/2075-163X/8/5/201

(k) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325463737_Characterizing_Rock_Art_Pigments

(m) ttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/325463737_Characterizing_Rock

_Art_Pigments

(o) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12520-021-01397-y

(p) https://www.mdpi.com/2075-163X/8/5/201

(q) https://viva.pressbooks.pub/arthistory/chapter/cave-painting/

(r) Moore, Jerry D. (2017). Incidence of travel: recent journeys in ancient South America. University Press of Colorado. doi:10.5876/9781607326007. ISBN 978-1-60732-600-7. JSTOR j.ctt1m3210q. LCCN 2016053403. OCLC 973325343.